Moab has nine years left to conserve a lot of water; and more

Utah expects its southeast region to reduce water usage 20% in 15 years.

Virtually nobody in Moab uses water pulled from the Colorado River, yet all the water the valley consumes counts against Utah’s share of the river’s flows.

The Colorado River Compact, signed in 1922 by the seven states with access to the river, sets limits on how much water each can use in any given 10-year period. The compact concerns not just water in the Colorado River but all the water in its tributaries, such as the Green River, and even groundwater within the watershed.

That means every well withdrawal made in Grand County counts as much as a withdrawal from the river.

Any consumptive use that we have with in the Colorado River Basin has to be counted, so that would include groundwater uses.

Scot McGettigan, interstate streams manager for the Utah Division of Water Resources, April 6, 2021

Fortunately, Utah does not appear to be at or near the brink in terms of its consumption of water in the Colorado River Basin, though future-looking and some localized concerns exist.

For example, the Cedar City Valley got word in January from the Utah Division of Water Rights that it faced the task of reducing its water usage by 33%. How quickly that will happen is unknown.

It will be no small feat. If everyone in the valley used the full amount of the water right they currently hold, it would nearly double the amount of water currently being pulled out of Cedar City’s aquifer.

In Moab, a much less dire situation exists, according to state engineers.

Moab currently sits within the safe range

The valley collectively is below its safe yield for the time being and could safely pull between 50% and 100% more water, according to the engineers.

The safe yield is the amount of groundwater the area can use without compromising its natural water systems. The Division of Water rights is currently working with numerous Moab stakeholders to develop a water management plan for the valley, at which point, the safe yield will be finalized.

However, state and locals don’t want to waste the resource, especially not in Moab. In fact, The Division of Water Resources released a plan in 2019, formed with the participation of Utah’s counties and municipalities, that accelerates water conservation goals set by former Utah governors by about double.

The area’s path forward

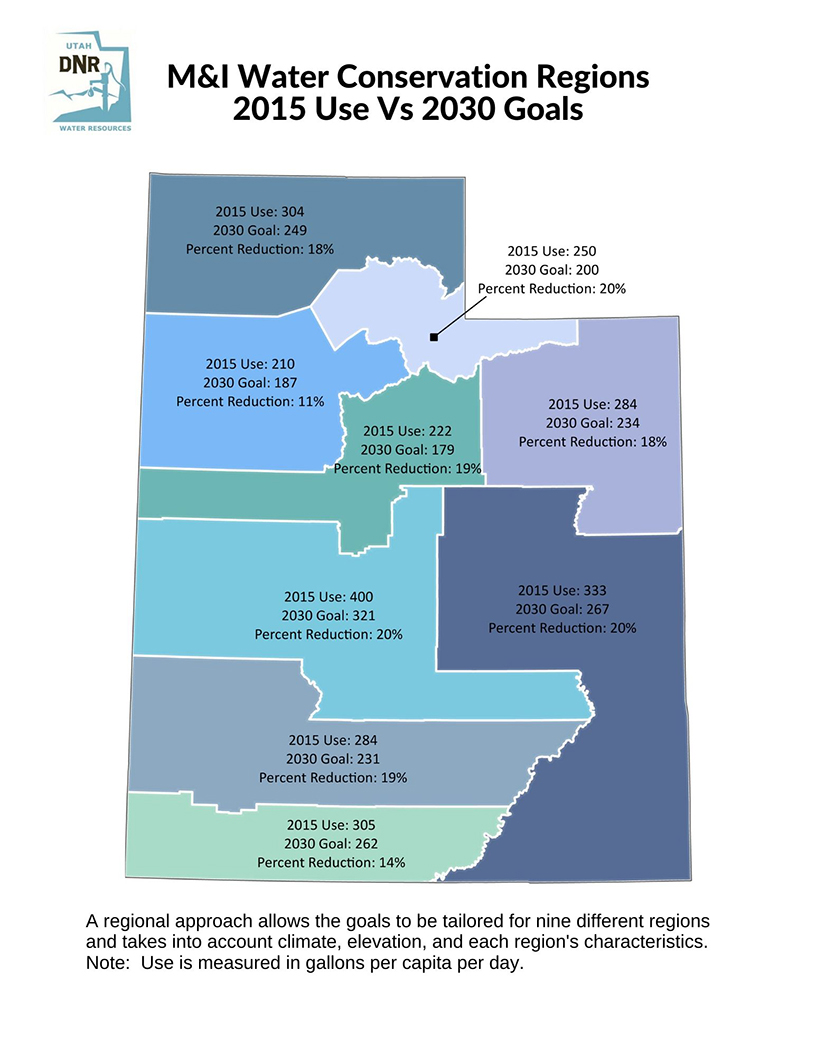

The 2019 plan, which sets goals for various Utah regions, calls for Carbon, Emery, Grand and San Juan counties to collectively reduce their per person water usage by 20% by 2030, based on 2015 usage.

In other words, the region has 15 years to become 20% more water efficient, per the division’s plan.1

Graphic by the Utah Division of Water Resources, dedicated to the public domain

The regional goals are a replacement to a statewide goal set by former Gov. Gary Herbert in 2013. In his State of the State address that year, he called for Utah to reduce its per-capita water usage 25% within 12 years.

At the time, that was an acceleration of a goal set in 2000 by former Gov. Mike Leavitt to use 25% less water in 50 years. By contrast, the 2019 regional goals would see Utah reduce per-capita water usage 16% in 15 years — more than double the rate Leavitt proposed in 2000.

When you look at the amazing variety we have in our great state – from southern Utah’s red rocks to the Alpine mountains in the north – targeting goals for a specific region allows the goals to account for things like climate, elevation, growing season and specific needs. It’s a more local and customized approach.

Division of Water Resources Director Eric Millis, Nov. 25, 2019

The goals won’t mean that Utah uses less water in 2030 than it did in 2015. The state’s population is expected to grow faster than its water efficiency, so Utah will continue to use more water overall.

However, the state is looking to tighten its belt and count acre-feet like they are dollars in a shrinking budget because, in many ways, they are.

Planning for a smaller Colorado River

The division expects the availability of water in the Colorado River Basin to shrink over the coming years due to greater evaporation and other water-related effects wrought by climate change.

While in recent years, it has had 1.725 million acre-feet of water from the basin available to it, the division plans for the state to use no more than 1.4 million in coming years. Currently, the state uses about 1 million acre-feet of water from the Colorado River Basin annually.

Moab’s water usage accounts for a sliver of the basin as a whole. The valley has roughly 14,000 acre-feet of groundwater discharge each year, and only part of that goes toward human consumption. That’s according to calculations by scientists with the U.S. Geological Survey.

Nonetheless, Moab and its neighbors each have a role to play in meeting larger goals of reducing water usage across the whole basin — an effort that is likely to impact a generation of people in one of the most-visited areas in one of the country’s fastest-growing states.

What Utah’s large water conservancy districts are working on

As part of reporting that water story up there, I got a hold of a list of projects that water districts across Utah were working on as of January.

It’s kind of funny that some of these conservancy districts are working on projects… that aim to pull more water from the ground.

Water quality in Moab is… fine?

As I was reading the recent Consumer Reports special about drinking water quality, I stumbled across a tool they created to help people learn about the quality of their drinking water.

The tool advises that municipalities offer annual updates on the quality of their drinking water. When I went to check for Moab’s, I found that there hadn’t been a report published since 2019 (reports regard the year prior).

However, the city added the 2019 report in response to an inquiry I made to them about it, and Moab City Communications and Engagement Manager Lisa Church told me that the 2020 report was in the works.

The 2019 report shows that the city is below the maximum contamination levels set by the U.S. Environmental Protection agency. However, the report did not include information about arsenic or PFAS.

When I asked about arsenic, Public Works Director Levi Jones said that the city tested for arsenic in 2019 and found levels ranging from 0.6 to 0.8 parts per billion (ppb).

Compare that with the EPA’s maximum allowed, which is 10 ppb, and Consumer Reports’s maximum, which is 3 ppb.

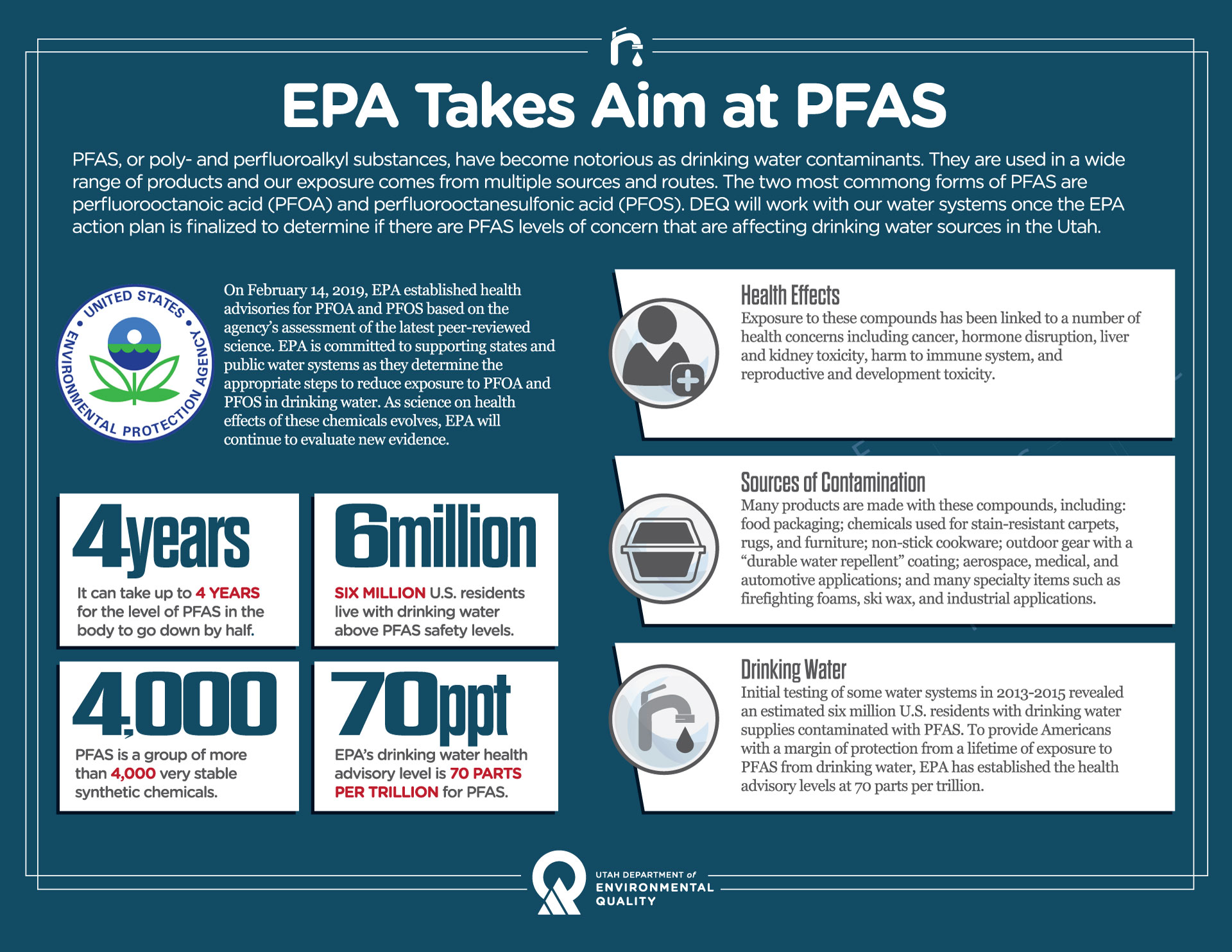

Regarding PFAS, the EPA has an advisory limit of 70 ppt. The Utah Department of Environmental Quality tested for the compound between 2013 and 2015 and didn’t find any.

Graphic by the Utah Department of Environmental Quality, dedicated to the public domain

While Utah has never produced PFAS compounds, many industries in the state likely use PFAS in their manufacturing processes. Military installations and airports in the states have likely used firefighting foam that contains PFAS.

Drinking water samples collected at Utah public water systems from 2013-2015 under the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR) did not measure any PFAS above 70 parts per trillion (ppt), but EPA and other states are looking at testing for PFAS with more refined analytical techniques capable of detecting PFAS at lower concentrations.

Utah Department of Water Quality, April 21, 2020

More on PFAS

The EPA has set a lifetime health advisory limit (LHA) of 70 parts per trillion (70 ppt) for PFOS and PFOA under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), but the agency has not set Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) for these compounds, an action that would require routine monitoring of public water supplies.

PFAS are not currently listed as hazardous substances under the Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA). No PFAS compounds are listed as hazardous wastes under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, nor are they regulated under the Toxic Substances Control Act. PFAS compounds are not listed as toxic or priority pollutants under the Clean Water Act.

Utah Department of Environmental Quality webpage on “PFAS Basics”

HDHO developers file appeals

I just need to read these and report on them, but so far, I have done neither. Sigh.

For archival purposes: the Magneto off-road in Moab

About a week ago, I asked a media contact at Jeep (actually, its parent corporation, Stellantis) for photos of the Jeep Magneto in its natural habitat — off-road in Moab. The newspaper never published the photos because they just got lost in the sauce.

Here are the photos Jeep sent me.

Photo by Stellantis, not licensed for reuse

Photo by Stellantis, not licensed for reuse

Photo by Stellantis, not licensed for reuse

A little more on waste management in Moab going public

Evan Tyrrell, the manager of Solid Waste Special Service District #1, told me last week that he sent a letter to the Moab City Council in late March explaining some stuff about the acquisition of Monument Waste.

I haven’t read it, but it would be nice to before a version of that report I linked publishes in the newspaper this week. Only one of a million things I’d like to do today even though it’s almost 7 p.m.

Update from Albrecht

Sen. Carl Albrecht sometimes sends out updates on what he’s doing. His office sent one out today. I’ll give the disclosure that I gave last time that I have not fact-checked this resource.

In other news (outlets)

KZMU: A Natural Gas Operator Begins a Different Type of Extraction: Bitcoin

This story looks like it’s part of a content sharing thing of which KZMU is a part. I think the original story might be out of Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

Basically, an oil extractor had been flaring because of a pipeline shutdown, and then after complaints about the the flaring, they turned the unused oil into blockchain mining.

I think people have been circulating a take that bitcoin is bad because oil extractors dedicate their operations to mining. This case, at least, seems to be one in which the operator did mining instead of flaring.

I should add that simply turning off the extraction activity, ostensibly, is not an option. I don’t really understand why; I’m sure there’s some interesting digging to do on that subject.

Anyway, whether bitcoin mining is more productive than flaring is left as an exercise for the reader.

KZMU: News from Tuesday, April 13, 2021

Molly listened to the meeting yesterday about OHV noise — the first of three scheduled for this week on the subject. Her takeaway was that OHV businesses in town are fine with some of the restrictions, but the limit on fleet sizes is really getting their goat.

As I recall, that was a subject on which Grand County Commissioner Kevin Walker was willing to get loose. It seems like, if anything in the ordinances are going to change at this point, that will be it. At least on the business license piece.

On the noise ordinance side, Grand County Attorney Christina Sloan said that she didn’t think the general noise ordinance changes were ready to pass yet. I don’t know exactly why; she probably said in today’s meeting (to which I have not listened).

I have 4.5 hours of OHV discussion to listen to. At 2x speed, that’s more like 2.5 hours. Ugh.

-

The original link for the following image broke and has been replaced. ⤴